No products in the cart.

Desperate Battles

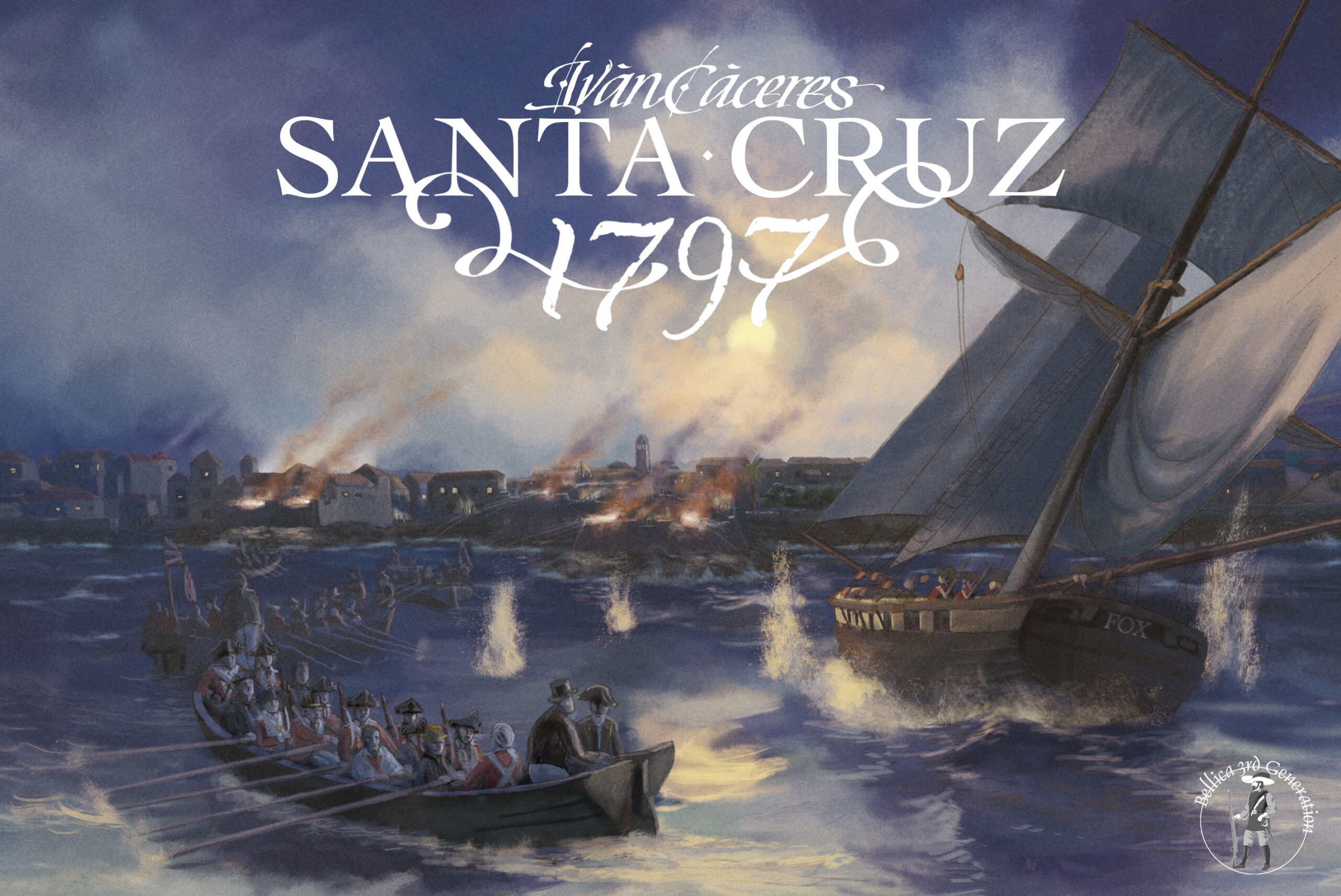

The “family,” not series, of DESPERATE BATTLES began with the excellent game designed by Iván Cáceres and published by us in 2017. Santa Cruz 1797.

Since the idea was so good, we couldn’t let the game system be limited to that one product. That’s why I designed “Von Manstein’s Triumph” and “Castelnuovo 1539,” both games published by other publishers, as well as two more that we will publish ourselves: “November Crisis,” about the battle of Madrid’s University City in November 1936, and “Fort Vaux,” about the battle for the fort of that name in the perimeter of the city of Verdun in June 1916.

What makes this system so interesting that it led me to design four games? The intensity of the gaming experience it provides. From a furious nighttime urban battle in the 18th century to the fortifications around Sevastopol, the game system (blocks, card-driven engine, combat-focused gameplay, and highly interactive) allows us, with a small or medium footprint game, to simulate truly desperate situations where victory is achieved after much effort and suffering, no matter which side you are on. Both players—since these are two-player-only games—have many alternatives and a lot of interaction, as both sides can intervene in the opponent’s Action Phase in various ways.

They are block games, so the fog of war is guaranteed in a combat environment that is often chaotic and uncertain. Since the game system, although not identical in all the games, is focused on combat management, the lack of knowledge about the strength and identity of enemy troops adds an element of uncertainty that you must consider when deciding what to do.

They are card-driven games, which means that to perform actions on the board, you must play cards, but they are not “CDG-type” games like those published by other companies. In reality, the cards define actions—some cards can only be played to execute a single action, others allow for more, and some are just events that occur when drawn from the deck—and you can execute them during your Action Phase. Some are even meant to be played during your opponent’s Action Phase, so this card-driven system brings uncertainty and interaction to the game—you don’t know what the other player has in their hand, and it is the cards that allow you to interrupt your opponent’s actions and intervene in the combats, even during their Action Phase.

As I have already mentioned, this model focuses on conducting operations and combat. Each game has its own system for resolving battles, tailored to the specific battle it represents and the design of the game it is part of. Therefore, other aspects such as logistics, reinforcements, political or strategic influences are left out of the model and, at most, are reflected in some of the cards and unique rules that each game has.

With this family of games, I aimed to address truly desperate situations that invite furious and frantic action. At the same time, I wanted to offer five battles with different settings and styles to showcase various aspects of the model and provide different gaming experiences for enthusiasts: A brutal battle for an underground fortress in the mud of the 1916 trenches, where the famous German Stormtroopers led the assault on Fort Vaux; a nighttime amphibious landing on a fortified 18th-century city, defended by a handful of Spaniards, vastly outnumbered and outmatched; the final assault on the port-fortress of Sevastopol in 1942, where a well-entrenched Soviet army had to be driven out of their positions by a well-equipped and well-led German-Romanian army, but one that lacked the time to complete its mission; a full-scale 16th-century siege in which 3,500 Spaniards made the 50,000 Ottomans who attacked them pay dearly for their victory; a 20th-century urban battle among the buildings of Madrid’s University City, where two armies fighting with the same doctrine and the same scarcity of resources had to make up for their structural deficiencies with courage and heavy losses;

They are games with a contained duration, ranging from an hour and a half for Santa Cruz 1797, Castelnuovo 1539, or November Crisis to 3–4 hours for Von Manstein’s Triumph or Fort Vaux. Similarly, their rules are not extensive, and once you have played one of them, you will find familiar elements in the others, allowing the learning curve for the new game to rise quickly.

That is why they are not just for veteran wargamers but for any audience interested in wargames and the history they represent. All of them include historical and design notes that help the player understand how and why the rules and elements of each game reflect history. They also serve as a good source of information—along with the bibliography included at the end of each game—to learn more about a specific period or military action, particularly Spanish military history.